Understanding Data as a New Form of Capital

Today the role of science and technology has become more important than ever. Digitalisation is playing a key role in this change. But digitalisation is fuelled by data, which therefore has become a factor of production equally important as capital. In fact, data is a form of capital, but with some specific distinctions. As such, it opens up new opportunities, but also harbours certain risks.

As of the end of last century, computing, electronics, and robots replaced the human with regard to improving productivity in almost every sector of the economy: technological innovation was “simply” the process of making this mechanism more efficient. What is different today, compared to the end of the twentieth century (and all periods before), is precisely the creation of an increasingly massive amount of data, usually referred to as Big Data. The emergence of data is both the result and the enabler of a complex interaction between technological evolution, industry trends, and societal/economic impact. This increasingly rapid and strong interaction enables changes in the very nature of both technology and the value creation process. We have been hearing every day for several years now that “data is gold” or that “data is the oil of the twenty-first century”. The simplest reasoning tells us that data are a form of capital. The nature of “data capital” is different from that of capital as we traditionally know it. The main difference between “data capital” and classic capital is ownership. The latter, by its nature, belongs to a single organization or person at any one time, while data can be accessible to several people and organizations at the same time. Further, data, being more fluid by nature, are more easily accessible to users.

“Data Capital” is Changing the Game

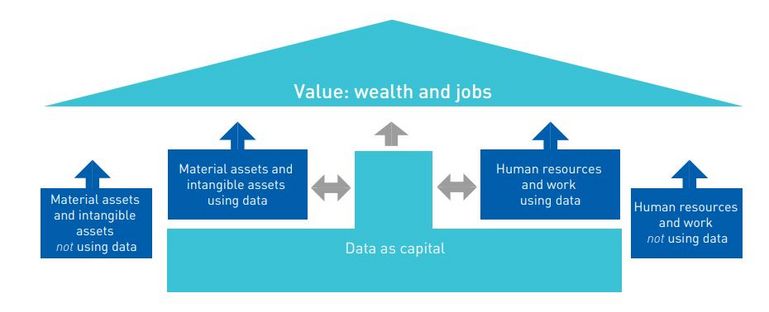

“Data capital” is a new element in the usual interaction (whether cooperation or competition) between classic and work capital. Today: it intervenes in the interaction between classic capital and work (whether cooperation or competition) and modifies it. If used properly, “data capital” can leverage both classic capital and work. It can play a multiplier role, toward traditional capital as well as towards the labour of those actors who apply their own technological knowledge. These include individuals, regions, and structures (private or public) that have access to a scientific and technological education and environment. The impressively high incomes and fortunes of some of the people involved in the digital companies of the Silicon Valley adventure illustrates the importance of the leverage effect of data access on classical capital.

Data as a form of capital that can leverage assets and human work cannot be universal.

Two Contradicting Trends and One Major Risk

Two trends are becoming evident: Firstly, the ensemble of mechanisms that seem to influence value creation and leverage due to data create opportunities for flexible and fast-moving individuals and organizations, when conditions (capital, training, business environment) allow. These conditions are concentrated in a limited number of places around the globe. Secondly, “data capital” is much more mobile than material capital and human resources and this fluidity makes it possible to create opportunities in a wide range of places around the globe. Education and training are becoming, simultaneously, a driver of opportunity and a source of division, separating regions of the world and dividing people with better or worse access to such education and training—access that is unequally spread around the globe. As a consequence, “data capital” radically modifies competition and creates new forces that can potentially unbalance incomes between geographical regions and population groups. An additional driver for a growing imbalance is the fact that data are much more useful for large organizations (companies, institutions, or countries) than for small ones. A large company has two inherent advantages: (i) it can more easily collect and access data and thus build up a larger capital base, and (ii) through the multiplier effect, large companies can produce a greater leverage effect on their reserves of classic capital. Hence the increasing risk of creating imbalances and concentrating power.

Information

Dr. Georges Kotrotsios, georges.kotrotsios(at)csem.ch

The Autor

SATW member Georges Kotrotsios is Vice President Marketing and Business Development, Member of Executive Board of the Swiss Centre for Electronics and Microtechnology (CSEM). CSEM is a private, non-profit Swiss research and technology organization focused on generating value for a sustainable world. Georges Kotrotsios studied electrical engineering at Aristotle University in Thessaloniki and at the Institut polytechnique de Grenoble, where he obtained a Ph.D. in optoelectronics. Furthermore, he holds an MBA in technology management from the University of Lausanne.

- Tags:

- digitalisation

0 comments